World Wetlands Day (02.02.2016) in Estonia

The annual World Wetlands Day (2 February) in 2016 year was a pretext to organize, by the Estonian NGO – Estonian Fund for Nature – an international conference in Tartu in Estonia, titled “From the usage till reconstruction of wetlands”. I have participated as the representative of the Naturalist Club, with the presentation of experiences of alkaline fens (natural habitat 7230) conservation in Poland.

The day before the conference, the participants had the opportunity to visit the Soosare bog, still in snow and ice. It is a raised peat bog ca 1,500 hectares big, surrounded by the bog pine forests on the slopes of the bog cupola. Part of the bog was drained and digged for peat exploitation between XIX century and 1990 year. After abandoning the peat digging, the bog vegetation regenerates. Estonian Fund for Nature in 2012 start conservation measures, blocking the ditches. Further actions, as blocking ditches more and partial removal of trees on the slopes of the cupola , are foreseen soon. An interesting element of the field visit was a show of drone use for bog monitoring. It is used for inspection of ditches and dams and for shooting from the air bog vegetation coverage. One battery and 20 minutes is enough to control 8 km of ditches, which requires several hours of inspection by traditional technique.

In the exact Wetlands Day (February 2nd), the conference was organized. It was started by the representative of the Ministry of Environment of Estonia reminder of the role of the mires in the life of Estonians: their beauty, significance in everyday life, but also the role in historical wars, and especially in the activities of the guerrilla. February the 2nd is for Estonians not only the anniversary of the signing of the Ramsar Convention, but also the anniversary of the signing of the Treaty of Tartu, where in 1920. Soviet Russia accept the independence of Estonia. Representative of the Ministry reminded how much the bogs were important in the war before the Tartu Treaty. No wonder that also contemporary Estonia has a national strategy for management of peatlands, including a strategy to restore them.

A representative of the Estonian Peat Association tried, however, to convince the participants that the economy is more important than defense, and that Estonian bogs should be exploited, although only in a sustainable way. He stressed the peat industry inspired the first bog research at the beginning of the twentieth century. The peat is in Estonia used as fuel material (for the climatic reasons, it is considered better to extract the peat from degraded peatlands and burn it in a power plant, than to let that the peat to oxidize in the bog). The peat is also exported. Peat is not considered here as a renewable material, there are annual limits on its acquisition. Bogs are evaluated in the national scale, starting or increasing of the excavation is possible only on degraded bogs with no natural values.

Andreas Harbel from the German Succow Foundation presented, however, the idea of paludicuture – various forms of economic use of wetlands, assuming maintenance, and even restoration, their swampy character, preserving the carbon resources stored in peat.

Two large LIFE ongoing projects are presented: conserving selected mires in Latvia and Estonia. Some implemented projects of rivers restoration (restoring the oxbows connectivity with the main river curent, restoring the old meandering river bed), so as the experience of restoring and managing the coastal wetlands on Estonian Baltic seashore, were also presented.

Latvian hydrologists present their experience of hydrological studies on raised bogs. Use of LIDAR terrain modelling and runoff modelling were presented. The records of water level changes in the bog, depending on the depth of piezometer, were especially interesting.

Some presentations were targeted to the conservation of wetlands supplied by underground waters: the alkaline fens (natural habitat 7230), mineral-rich springs and spring fens of Fennoscandia (natural habitat 7160), petrifying springs (natural habitat 7220). Also my presentation on Polish experience of alkaline fens conservation belonged to this thread. Examples from Latvia, Sweden, Polish and Estonian confirmed outstanding natural value of such wetlands, but also emphasized the considerable difficulties with their protection and restoration. The hydrological conditions are of particular importance, but the hydrology is always complex and not easy to recognize. Sometimes, the necessary conservation measure is to fill the ditch located on the mire by permeable peat to restore the infiltration of groundwater. Restoration of degraded fens of this type is practically impossible. Sometimes it is possible to restore suitable habitat for some of the fen species, but not the functioning fen. Climate change may affect the temperature of groundwater, which in followed by changes of transport of substances dissolved and by alteration of the whole fen biogeochemistry.

An interesting part of the conference was the block of presentations, presenting negative impact of the shale oil exploitation (Estonia specific energy resource) for the wetlands and their hydrology.

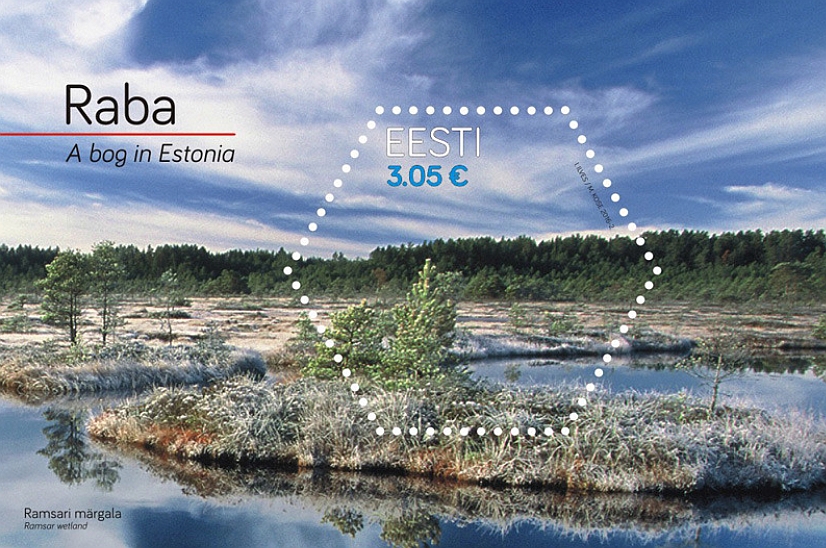

One of the element of the Estonian LIFE bog project is also creating of the database of the bogs motives in the Estonian literature and art, for later use in educational activities. Interested examples were presented. Also the Estonian Post celebrated the Wetlands Day with the release of a the post stamp with the bog landscape.

The presentations of the conference are available at:

http://www.elfond.ee/et/teemad/raba/2016-01-05-10-57-37/ettekanded2016

Paweł Pawlaczyk

Drone starting on Soosaare bog. By Krisjanis Libauers.

The field discussion on Soosaare bog. By Mara Pakalne.

Landscape of the Soosaare bog. By Mara Pakalne.

The famous fountain on the market in Tartu in February rain. Dorpat (Tartu German name) in the sixteenth century was the Polish town – The King Stefan Batory granted the town the white-and-red flag and founded a school, which later developed into a famous university. By P. Pawlaczyk

Post stamp of Estonia Post with the landscape of peatbog.

This text is also available in: PL